Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

This is the second and final part of my analysis concerning the smallest (revenue) university currently participating in the NCAA’s top athletics division (BCS).

As mentioned in the previous post, it was reported last week that the University of Louisiana at Monroe posted total athletic revenues of $15,568,952 while its expenses amounted to $16,927,856, resulting in a deficit of $1,358,904 from July, 2018 through June, 2019.

With UL-Monroe already at the bottom of the revenue charts for the 130 schools competing in the upper tier of college athletics, it might be a good time to pause and reflect on matters going forward.

The ULM Warhawks moved up into the NCAA’s equivalent of the big leagues (formerly Division 1 – now known as the BCS) in 1994. The football program proudly points to a 21-14 victory over a Nick Saban-coached Alabama Crimson Tide in Tuscaloosa in November, 2007. For the next year, billboards adorned Interstate 20 in northern Louisiana to celebrate the Warhawks’ signature football win.

Alas, in the 26 years since moving into the upper ranks, the school’s football program has fielded just one winning season (8-4 in 2012) and one bowl game appearance during that time.

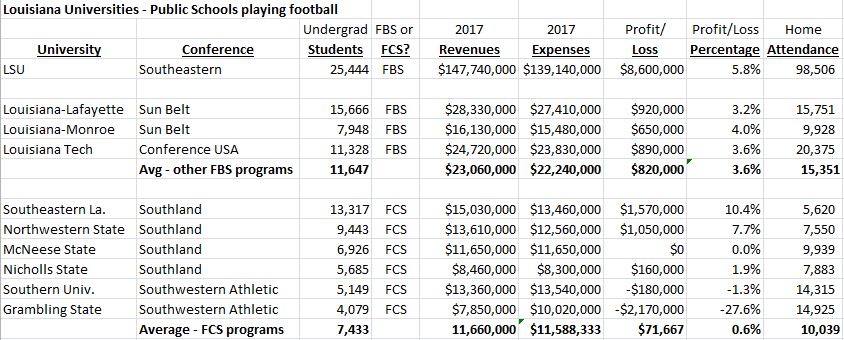

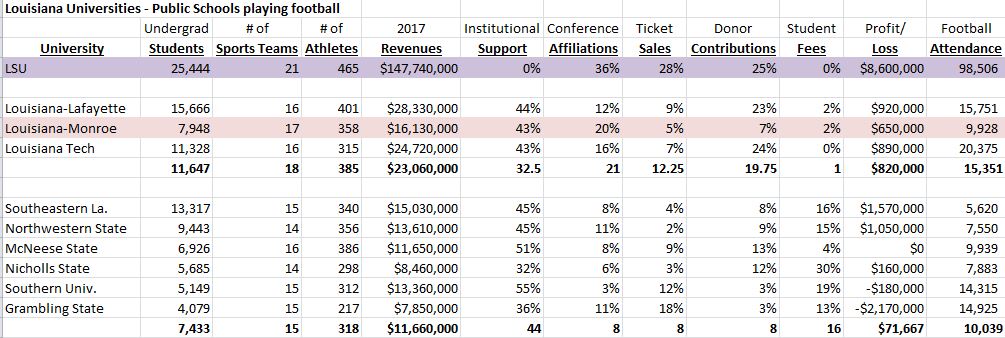

The football-loving state of Louisiana has ten public universities which field college football teams. One other (Tulane University) is a private school and has been omitted from this analysis.

Louisiana State University, the newly-crowned BCS champions of college football, raked in nearly $158 million in athletics revenue and usually posts a healthy annual profit. The college football program financially supports all other sports teams (men and women) at LSU with the exception of men’s basketball and baseball. All other sports at the school lose money if measured on their own.

At UL-Monroe, the annual athletics revenues are just 10% of LSU’s sports budget and must be tightly managed just to break-even on a year-to-year basis.

A review of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics for the year 2017 showed that LSU fielded 21 athletic teams with 465 student athletes. In comparison, ULM supported 17 athletic teams with 358 student athletes participating in 2017.

With LSU’s 10:1 revenue advantage over ULM, let’s look inside the reasons for that huge financial edge.

LSU’s undergraduate student body of over 25,000 is more than three times larger than UL-Monroe (about 8,000). However, the average LSU home football game attracts nearly 100,000 fans per home game (almost 400% the size of the school’s undergrads). ULM’s home games averaged slightly less than 10,000 fans per game (or just 110% of the undergrad total).

Revenues from LSU’s large number of private athletic donors generated a whopping 23% of LSU’s annual revenues, while ULM’s sports donors contributed just 7% to the university’s significantly-smaller athletics budget.

There is no doubt LSU’s ability to deliver football success and a unique fan experience at those games have combined to create a powerful magnet for attracting ticket buyers to football games and thousands of private donors to the athletic program. A long track record of success gives a distinct advantage to the Tigers from Baton Rouge.

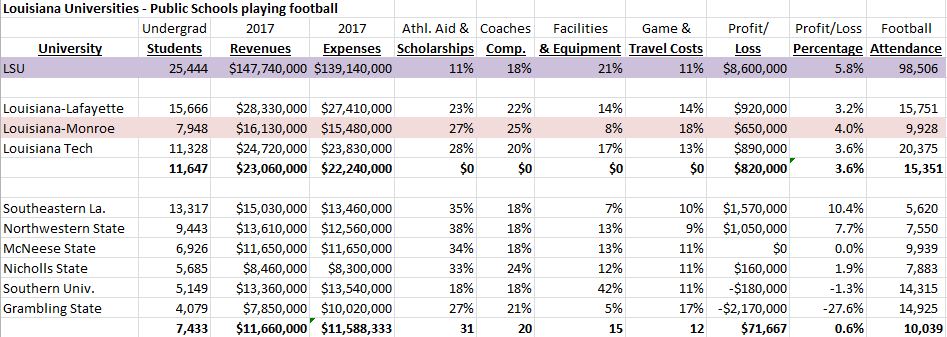

Let’s now examine the expense side of the ledger:

For UL-Monroe, the percentage of expenses attributable to athletic scholarships at the school is significantly higher (27%) than LSU’s 11%. The same goes for coaches’ compensation (25% vs. 18%) and travel/game day costs (18% for ULM vs. LSU’s 11%). However, you must consider LSU’s behemoth pot of financial resources which provides the Tigers sports programs more money to work with every year.

All things considered, the ULM Warhawks have done an admirable job on the field and in the accounting books during the 26 years since joining the so-called “Big Boys” of the 130-school BCS.

Unfortunately, the Warhawks and their football fans have become accustomed to trading away up to two home football games every season in return for “big money” road trips. ULM frequently becomes the homecoming opponent of a larger conference opponent in trade for around $1 million in guaranteed appearance revenue to help defray costs of the school’s athletics department.

The guaranteed money generated by those two road games dwarfs the revenues UL-Monroe makes from playing a home football game in front of a relatively modest crowd along the bayou in northeastern Louisiana.

In 2019, ULM’s football team took the road in successive September weeks to play at Florida State of the ACC and a game at the Big 12’s Iowa State. In 2018, the team played “money” games at both Texas A&M and Ole Miss of the SEC.

From 2004-2006, ULM had a unique “home” football game arrangement with the University of Arkansas. After two years playing the Hogs in Fayetteville, the Warhawks’ agreed to play their 2006 “home” game in Little Rock where 50,000 mostly-Arkansas fans attended.

Sadly, most Louisiana’s public college football programs not named LSU are forced to generate cash to fund their athletic programs in similar creative (but fan-unfriendly) ways.

After 26 years of participating in the upper division of college athletics, is it now time for UL-Monroe to consider other options?

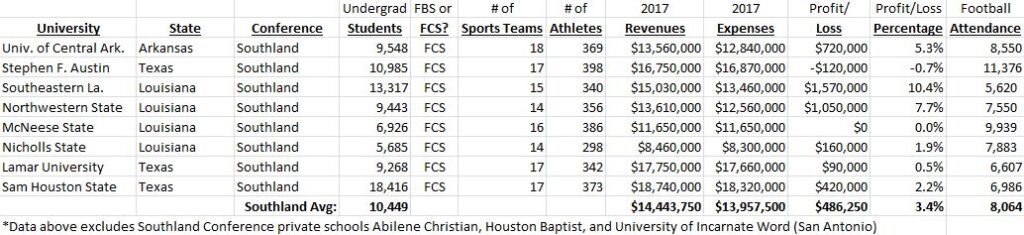

Prior to 1994’s graduation into the world of “big time” athletics, ULM participated in a smaller division (FCS – formerly known as Division 1-AA) sports league known as the Southland Conference.

Today’s version of the Southland Conference features several regional teams from nearby parts of Louisiana, Texas, and Arkansas.

Until 1994, the athletics programs of Northeast Louisiana University (which became ULM in 1999) had much success participating in the Southland Conference. The 1987 Northeast Louisiana college football team (which featured a future NFL quarterback named Stan Humphries) won the National Championship in Division 1-AA (now known as the FCS).

The only negative would be a step-down in football competition. ULM would no longer be playing for a traditional bowl game after the regular season. However, the cost of playing in many of today’s lower tier college football bowl games may exceed the revenues. Quite often, college football bowl games lose money for the athletics programs due to the costs of travel, hotels, food, and a bowl’s requirement to purchase a minimum number of tickets.

In football, the bigger opportunity for ULM in the Southland Conference would be to compete annually for championships and a chance to enter the 16-team FCS playoffs. Two members of the Southland Conference (Nicholls State and Central Arkansas) participated in the 2019 FCS football playoffs.

With the exception of football, the Southland Conference plays for the same post-season NCAA championships (basketball’s “March Madness” and NCAA’s Baseball Tournament) as ULM currently plays for as a member of the Sunbelt Conference.

The reduction in travel geography alone could certainly save the Warhawks a lot of money in all of its sports programs.

The return to playing in-state rivals such as Northwestern State University (Natchitoches), Southeastern Louisiana (Hammond), and Nicholls State (Thibodaux) could spark more local fan interest in all of UL-Monroe’s athletic programs. Fans of both schools would be just a few hours away instead having ULM play Sunbelt Conference games (in all of the school’s sports) as far away as North Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

The bigger issue in northern Louisiana is the perception of ULM continuing to play college football at the same level as their long-time I-20 rival Louisiana Tech.

The two schools were both members of the Southland Conference for many years through the 1980’s. In 1989, Louisiana Tech beat ULM to the punch as it decided to move up into the upper division for football and other sports.

The Bulldogs (who, by the way, have appeared in nine bowl games since moving into the BCS group in 1989) have not played UL-Monroe in football since November, 2000. The Ruston-based school’s administration (and, more likely, its largest financial benefactors) apparently believes there is now little to be gained by renewing the football rivalry with a long-time competitor located just 30 miles to the east in Monroe.

For UL-Monroe, the downside of returning to the smaller division FCS Southland Conference would be the tacit admission that they had finally “lost” to the battle for North Louisiana’s football superiority to bitter rival Louisiana Tech.

In reality, the students and alumni of ULM might be rejuvenated with a return to playing football for championships again and competing against some familiar schools and former rivals located within reasonable driving distance of Monroe, Louisiana.

Based on the modest size of ULM’s undergraduate student base, its limited financial resources, and base of loyal sports fans who may be tiring of losing, it might be the right time for the Warhawks to soar into the skies in search of a new but familiar home to nest once again.