Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

The spirit of Monty Hall is alive and well this week in college athletics. The man who was one of the creators and the original host of television’s long-running game show called “Let’s Make A Deal” passed away in 2017 at the age of 96.

The Big Dealer’s popular TV game show involved a trading floor of wildly dressed contestants (usually in some theme to gain his attention) willing to interact with the host for a chance at prizes. Monty Hall would present the contestant with one or more decisions as to which prize option to choose. In almost every case, one of the contestant’s possible selections involved taking a risk on trading a “sure thing” (such as cash) for an unknown prize behind a numbered curtain or box on the stage floor.

Sometimes the contestant taking the numbered curtain won a more valuable prize (like a major kitchen appliance). Other times, they received a “Zonk”.

That was “Let’s Make A Deal”’s way of presenting a silly worthless joke prize like a giant tricycle or a baby goat. You get the idea.

What does that game show have to do with college sports?

Plenty! On Thursday night, the NCAA (the overlords for most of college athletics) and a group of the largest athletic conferences agreed to accept a massive $2.8 billion settlement agreement in a pending lawsuit. This agreement will (hopefully) resolve a class-action lawsuit claiming theoretical back-pay due for about 14,000 (the number keeps fluctuating) former and current college athletes going back to 2016.

On average, that works out to be about $200,000 per athlete.

What started this lawsuit?

A former Arizona State University swimmer (Grant House) filed the suit demanding that college athletes (under the NCAA’s confusing “Name Image and Likeness” approval) should have started receiving their share of NIL loot while implementation was delayed for several years.

The attorneys involved in announcing Thursday night’s settlement agreement in “House vs. the NCAA” have been working for months to hammer out a mutually agreeable financial deal.

Why didn’t the NCAA just say, “Tough luck, buddy. See you in court!”

Though I am not an attorney, the consensus was that the NCAA may have been on the hook for as much as $20 billion in damages if this lawsuit was permitted to continue for years and the NCAA lost in a “worst case” scenario.

Just like most legal actions, the brave attorneys on both sides will bark loudly at each other early to make their clients happy (while paying the legal fees). A few months later, both sides become painfully aware of the mounting legal bills and realize that everyone (including the attorneys) might be better off taking a less-risky mutually agreeable deal today rather than spending years in the courts.

If the NCAA eventually lost a $20 billion judgment, it could have resulted in bankruptcy for the organization.

Who cares if the NCAA goes under?

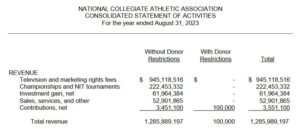

Good question! The NCAA, which lists itself as a non-profit organization, has its primary offices and about 500 employees located in Indianapolis, Indiana. One of the NCAA’s primary jobs is to conduct championship events for college athletics (at a profit, of course). The lone exception is the quite lucrative Division 1 College Football Playoffs. The BCS football schools keep that revenue and split the net profits outside the purview of the NCAA.

The NCAA is comprised of about 1,100 member institutions. According to its website, 350 schools are considered to be part of Division 1 with another 310 institutions making up Division II and 438 colleges in Division III.

With annual revenues of more than $1 billion per year, the NCAA redistributes about 60% of its loot back to the member institutions. The remainder is kept to pay for other programs and, of course, its own costs of administration.

The bulk of the NCAA’s income is derived from its ownership of the annual March Madness college basketball tournaments for men and women. The television money (like in most sports) for those events has skyrocketed in the past decade.

The NCAA has also been keenly aware that the top 60-or so major colleges in today’s four largest conferences (SEC, Big Ten, Big 12, and ACC) have been making comments about potentially leaving the NCAA and its thick, burdensome and poorly enforced rule book. If the remaining Big 4 conferences should decide to skedaddle and form their own association, the NCAA’s remaining member schools (though numerous) simply do not generate enough money into the coffers to sustain the organization’s current size and structure.

Keep that in mind as you ponder the rest of this story.

Who is going to pay for this this newly confirmed $2.8 billion settlement agreement?

- The NCAA itself – $1.1 Billion – to be paid out of future revenues over the next ten years

- The major conferences (SEC, Big Ten, Big 12, ACC and Pac-12) – $664 million – paid over the next ten years. (Note – the now-extinct Pac-12 is included because the lawsuit covers money “owed” to athletes beginning in 2016)

- The other 27 NCAA Division 1 Conferences – $990 million – paid over the next ten years

The first installment becomes payable beginning in the fall of 2025.

In return for this boatload of future money, the plaintiffs will drop the lawsuit. There are several other implications including future “caps” on athletes’ NIL money, but let’s save that for another discussion.

On the surface, it would appear that every party in the settlement will pay a significant portion of the “go away” money to end the lawsuit. That’s where the problems begin.

If the major conference schools (which receive significant incremental cash from the College Football Playoffs) are the schools which paid the majority of NIL money to these college athletes, why shouldn’t they be asked to pay the majority of this settlement money?

That’s exactly what the other 27 smaller NCAA conferences want to know today.

Apparently, the smaller athletics conferences were either not represented or under-represented at the settlement bargaining table while the framework for the current offer was being put together. The majority of these smaller conferences (like the rest of us) have only recently learned some details about this deal.

That seems shady. Why would the NCAA and the Big Conferences keep them out?

The smaller conferences were apparently being represented by the NCAA itself. Since the schools receive a portion of the NCAA’s redistributed financial pie every year, they were probably not perceived as a serious threat to jump ship and leave the organization (yet).

Remember, the percentage of the NCAA’s total revenues derived from the smallest conferences simply doesn’t match-up with those coming from the Big 4. The NCAA is playing friendly with the biggest names in college sports, because that group of schools has the most financial motivation and wherewithal to bolt from the organization at some point soon.

Doesn’t the NCAA understand that many of the smaller schools’ athletic budgets cannot absorb a significant loss of revenue?

The NCAA was quite aware that member schools playing in the smaller athletic conferences did not have the market power or the financial resources to derail this massive financial settlement. With representation for those 1,000+ schools effectively locked out of the negotiation room, the NCAA appeared to be more concerned with its own self-preservation rather than allowing its largest group of member institutions to be steamrolled in the settlement.

The smaller schools will soon feel a double-whammy.

The NCAA’s $1.1 billion payment over ten years equates to $110 million/year. As stated earlier, the NCAA has annual revenue of about $1 billion. Once the NCAA writes its annual settlement check beginning in 2025, there will be 10% less money available to redistribute back to member institutions. It normally pays 60% of revenues back to the member schools.

Let’s watch to see if the NCAA takes some of the medicine and scales back its operations. They may have the right to fund themselves first out of the remaining annual revenues.

Then there’s the $990 million portion of the settlement (over ten years) which will be due from the non-major conference Division 1 schools. That’s amounts to $99 million per year. Each of the smaller schools will feel an impact in their athletics budget to cover that payment, too.

Since many of these smaller conference schools are already struggling to remain financially viable, any significant loss of revenue beginning in the fall of 2025 will have more impact on them.

Expect a growing number of financially struggling colleges to reduce future travel expenses by realigning to play in conferences which make more geographic sense. Many of us fans would prefer to see the renewals of some old rivalries with teams from the same geographic region.

In some cases, the loss of funding may mean a reduction in the number of competitive sports being offered at some of these non-major colleges.

Now – It’s time to play the NEW “Let’s Make a Deal! – NCAA Settlement version”

Door #1 – The curtain in front of Door #1 is labeled, “Fight the Lawsuit”.

If the NCAA decided to fight this lawsuit in the courts over a period of years and prevailed in the case, the current college athletics structure would be saved (except for the millions in legal bills). If the NCAA ultimately lost the case, the current college athletics structure would be “Zonked” and forced to cough-up the $20 billion (plus legal costs) and head straight into financial oblivion.

Before we raise the curtain on Door #1 to show you what is behind that high risk strategy, you may prefer to try Door #2.

Door #2 – This curtain is labeled, “Quick – let’s settle this lawsuit ASAP!”

If your legal representatives do not recommend taking the risk in court, the best option to reduce potential exposure is by putting a lot of money on the table as quickly as possible and hoping the other side prefers immediate gratification.

This is what the NCAA and the large athletic conferences decided to do this week.

But…before making a decision between the current two options being presented, it might be time for one party to threaten to walk away from either one of these two deals.

Door #3 – This final curtain is labeled, “Who walks the plank first?”

The NCAA has effectively pitted the four remaining largest athletic conferences against the 27 smaller conferences on the fairest way to determine and split the costs involved in this settlement agreement. At the moment, the NCAA appears to have chosen to side with the largest conferences – even though the higher percentage of NIL money being paid to athletes was and will remain applicable to the largest schools.

Will the smaller conference schools reject the inequity of being kept in the dark about this agreement and then strong-armed to accept this negotiated settlement?

Should the smaller conferences threaten to sue the NCAA and leave en masse?

Come back soon as we learn whether the NCAA’s smaller conference schools agree to being financially “Zonked” in this settlement.