Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

In the coming days, Disney (stock symbol: DIS), the parent company of ESPN, may be reducing the headcount at its sports division once again. ESPN laid off about 300 on-air and technical staffers in 2020.

The parent company’s encore CEO Bob Iger (who returned to the company last November to help reverse the company’s flagging stock price) had indicated recently that more layoffs are forthcoming for Disney and its ESPN division.

All of this comes as Disney’s ESPN is negotiating a new contract to cover NBA basketball games. The new deal is expected to cost more than the $1.4 billion already being paid to the basketball league every season.

Of course, it makes no sense. “Fire the cameraman! We’ve got to save money to pay for NBA games!”

ESPN has lost its way and has boxed itself into a financial corner. How did this happen?

The Entertainment and Sports Programming Network (ESPN) was founded in 1979 during the early years of cable television. It immediately became a “must have” cable television channel for most of us sports fans.

When it was getting started, ESPN struggled to fill a 24-hour sports schedule in the early years.

They were starting from scratch. ESPN cut deals with small conferences to telecast college basketball games. The legendary Dick Vitale’s long career as a college basketball analyst began in 1979 in the early days of ESPN. Dickie V helped build the popularity of ESPN during its critical early years.

College baseball and softball games would become part of the early schedule. Tennis matches, sports car racing, fishing shows, rodeos, and nearly any athletic event (including cheerleading competitions) helped ESPN to fill its 24-hour schedule at a reasonable cost of production.

ESPN’s frequent “SportsCenter” programs provided Americans with an opportunity to watch video highlights from earlier college and professional games involving your favorite teams. If your favorite baseball or basketball team played a late night West Coast game, SportsCenter would eventually show the highlights and the final score.

Prior to that, you would hope that your local newspaper did not “go to press” before the West Coast games had been completed. Otherwise, you were out of luck.

In 1979, there was no significant competition for ESPN. Cable TV was in its infancy with only about 15 million subscribers nationwide.

WTBS in Atlanta started off the national cable television trend. The local UHF station went to satellite and became “The Superstation” in 1976. TBS turned the Atlanta Braves into mid-America’s baseball team from April through October. Founder Ted Turner later assembled the Cable News Network (CNN) to go national in 1980.

MTV (when they actually featured music) began on cable television in 1981. The Weather Channel debuted in 1982.

In those early days, The Weather Channel’s “Local weather on the eights” was actually true. Today, it means you have to wait until 18 or 48 minutes past the hour. (Do they really think we’re that dumb? Don’t answer that.)

Another early cable television favorite channel was the Madison Square Garden Network.

They famously provided a national television audience for Vince McMahon’s fledgling wrestling outfit called WWF (later WWE). The MSG Network also carried New York Yankees baseball and New York Rangers hockey games. It is now known as the USA Network.

However, it was ESPN which was able to execute a vision to become America’s premier sports programming network.

In 1979, the sports programming for the traditional “Big Three” networks (ABC, CBS, and NBC) was generally confined to Saturday and Sunday afternoons. The NFL and NBA were the exclusive domain of the traditional TV networks as local television signals covered most of the country without cost to customers. Major League Baseball was relegated to a Saturday afternoon “Game of the Week” on NBC. Good luck if your favorite teams weren’t the Yankees, Red Sox, or Dodgers.

Fox Sports? They did not come into existence for another 15 years in 1994.

During the 1980’s, ESPN’s skyrocketing popularity allowed the network to require local cable television operators to pay them a monthly fee based on the number of cable households in the local market. This was quite uncommon at the time. Did you know that your local cable television operator was being PAID by some of cable channels (like some of those home shopping networks) to carry their programming?

ESPN’s founders sold their fledgling operation to ABC five years later in 1984. ABC would late be acquired by Disney in 1996.

As ESPN’s popularity grew, so did the public’s appetite to see more sports on weekdays and at night on the weekend. ESPN was able to successfully bid for the rights to cover more and more college and professional sports. The network was more than happy to keep passing those additional costs along to customers at home.

Network fees charged by ESPN to cable operators have grown significantly over the years. It’s one thing to be charged an extra few dollars per month per household for your favorite sports channel and hope that your cable television customers won’t mind paying the extra money.

ESPN started to see more competition for the rights to broadcast major league sports and major college athletic conferences. To keep growing and provide sports viewers with their favorite sports at home, ESPN reached into YOUR pocket and paid dearly for the rights to NFL, NBA, NHL, MLB, and major college sports. To recover those ballooning costs, ESPN reportedly charges cable television operators about $13 per month per household for its family of sports networks.

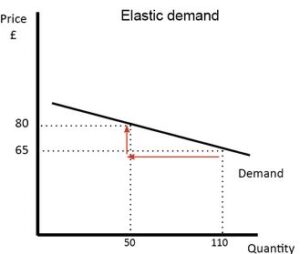

Economics 101 reminds us about the elasticity of demand.

Here’s an example. When your favorite pizza parlor charged $10 for a large pizza, you returned fairly often. When the price rose to $15 for the same pizza, you started to think about other options or simply didn’t go as often. Once the price climbs to $20, most of us will find a cheaper dining option. At some point, you will reach your limit and refuse to participate.

And that is where we are with ESPN.

Sure, they still provide customers with (generally) good sports programming. However, there comes a time when a service provider is now charging you more than you are willing to pay.

ESPN misjudged its customers and how much they were willing to pay for services. Cable television operators became faced with difficult choices, too. If they drop ESPN, will their customers drop by a proportionate amount?

As a customer, you get to open that monthly bill and make a judgment. How much is “too much” to pay for your cable television sports programming every month.

The rising cost has led millions of former cable television customers to cut the cord.

The market has been speaking in recent years. ESPN has not been listening.

ESPN believed that its customers would agree to pay higher costs to see the NFL, NBA, Major League Baseball, college football, the NHL, and other sports.

With cable television systems losing customers by the millions in recent years, ESPN’s base revenues are shrinking, too.

Disney recently reorganized its mammoth company into three divisions – Entertainment, Theme Parks, and ESPN. The prevailing thought has been that Disney might sell ESPN outright or, perhaps, try to spin-off the ESPN division as a separate stock entity.

That isn’t a “win” for Disney shareholders, though.

Suppose you owned 150 shares of Disney stock today. The company announces, “Congratulations! We are splitting up into three entities. You will now own 50 shares of Disney Entertainment, 50 shares of Disney Theme Parks, and 50 shares of ESPN stock.”

Disney’s combined market value would plummet as ESPN shares would be quickly dumped.

It appears that Disney may be stuck with ESPN right now. Unless…

Perhaps there is a wealthy corporation (Hello, Amazon?) willing to pay Disney to take ESPN off their hands. Even if the deal involves a loss for Disney in the short term, ESPN would become someone else’s problem.

ESPN has tried to become all things sports to all people. The market has changed significantly since its beginnings in 1979. The competition has increased and become tougher. ESPN’s viewership keeps dwindling. Don’t forget about the internet!. It promises to keep causing market disruptions for years to come.

In the meantime, ESPN just keeps on doing what it has been doing (even after laying off the poor cameraman, that is).

This story reminds me of the decline of former retail giant, Sears Roebuck & Company.

As Sears grew nationwide during the 1900’s, it continued to try to be all things to all people. Niche operators developed and nibbled away at portions of Sears’ expansive retail business. Over time, the company became too slow to respond to changing market conditions. It was a bloated and stubborn organization with significant overhead, debt, and not enough customers remaining willing to support it.

In the past two decades, store after store has closed. Sears has nearly disappeared from the retail landscape.

ESPN’s product life cycle peaked a long time ago. Will they become the next Sears?